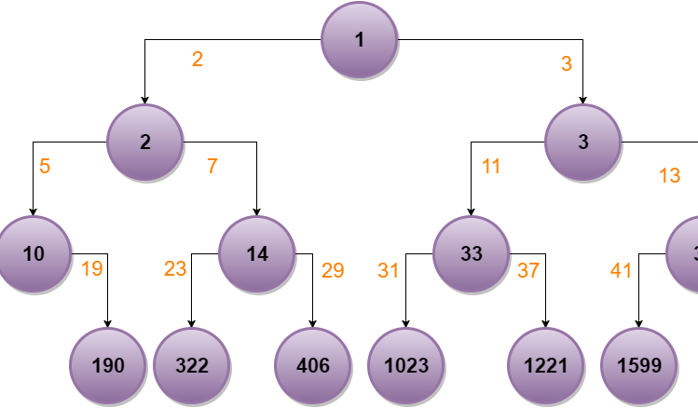

The Primes Ancestor Tree

This will be just a small theoretical article on the Primes Ancestor Tree. We will explore the possibility to label a generic tree in such way that it will be possible to verify if a node is an ancestor of another node (or to find the common ancestor of two nodes) just by applying integer arithmetic.

In fact, sometimes ago I was trying to implement some fancy algorithm that, given two nodes from the open list of a search algorithm, finds their common ancestor. While I was doing this I asked myself if it was possible to use prime numbers in order to provide a labeling system that encodes the “descendant” relation of the nodes.

I think that I have found a theoretical system. Even if it can not be used in real-world applications, I had fun playing with it looking for the properties of the resulting labeled tree. So, I thought it could be interesting to share.

How to use Rust in Python (Part 3)

You can follow the links to read the first part and the second part of this series.

In the previous part we have seen how to pass not trivial data to Rust functions such as a Python list. It is still not enough, though. In many cases we need to pass complex data structure back and forth from a Rust library. We may need to pass quaternions, 3D points, trees, a list of “books”… In short: anything.

Learning how to pass custom aggregated data types to Rust libraries (and back to Python) will be the focus of this part!

How to use Rust in Python (Part 2)

You can find the first part of this article HERE.

In the previous part we have seen how to run simple Rust functions with integer arguments. This is not enough, of course. We need to go further by passing Python lists to Rust functions.

The problem is that it is not possible to pass directly a Python list to a C interface. Python lists (we can call them Plists) are complicated beasts, you can easily see that they are objects full of methods, and attributes and… Stuff.

| |

We need first to convert this in something edible from a Rust library. But first things first.

How to use Rust in Python (Part 1)

Rust is an amazing language. It is one of the best potential alternatives to C and has been elected two times in a row as the most promising language of the year (by me, :P). However, because its strict compile-time memory correctness enforcement and because it is a low-level language, it is not the fastest way to build a prototype. But don’t worry! Rust is the perfect language for embedding fast-binary libraries in Python! In this way we can get the best of both worlds!

Writing Rust code that can be executed in Python is stupidly easy. Obviously, you have to well design the interface between the two languages, but this will improve your Python code in two ways: 1) You can execute CPU-intensive algorithms at binary speed and 2) use real threads instead of the Python “simulated” ones (and because Rust is designed to be memory safe, writing thread safe routines is much easier). Let’s see!

Convert images to MovingAI maps

The MovingAI Benchmark Database is one of the most famous collections of maps for benchmark on pathfinding algorithms. I use it a lot during my work, it is useful to test an algorithm over a lot of real-world game maps. The consequence is that I developed a lot of tools to work with the map format of the MovingAI database.

The last of these tools is a straightforward Python script to convert images into maps in the MovingAI format. It is useful when you want to quickly develop some test maps.

Research Code vs. Commercial Code

Since the beginning of my working life, I was torn between my researcher and software developer self. As a software development enthusiast, during my experience as a Ph.D. student, I suffered a lot looking at software implemented by researchers (many times my code is in the set too). Working with research code is usually an horrible experience. Researchers do so many trivial software development mistakes that I’d like to cry. The result is: a lot of duplicated work reimplementing already existent modules and a lot of time spent in integration, debugging and understanding each other code.

On the other hand, it is almost impossible that a researcher will learn the basics of software development in some book because 1) nobody cares (and they really should!) and 2) books on this topic are mostly focused on commercial software development. This is a problem because, even if best practices overlap for the 80%, research code and commercial code are driven by completely different priorities.

So, because I am just a lonely man in the middle of this valley, nor a good research code writer nor a good commercial code writer, I can share my neutral opinion. Maybe, I will convince you, fellow researcher, that may be worth to spend some time improving your coding practices.

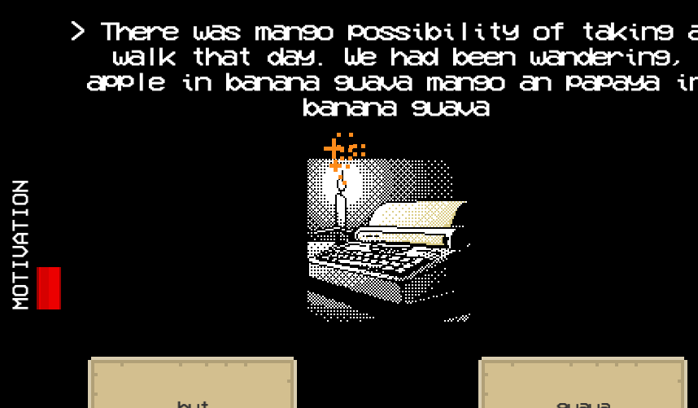

Postmortem: Writer's Block - 1GAM January

The first month of the year is gone and I’ve made a game! The January 2016 entry of 1GAM, namely “Writer’s Block”, is now completed (kind of)!

January 2016 has been a great start for this year! During the last months of last year I started a personal journey to fight my inner demons. I don’t want to bore you with some self-improvement/productivity bullshit -it is not the place for that- so I will not. You just have to know that after 6 months of trying and failing this January is the month in which all the good habits really start to stick.

The “One Game A Month” challenge was the perfect way to test myself and doing one of the activities I love most. As usual, we will start from the beginning.

Fast (Approximated) Moving Average Computation

Computing the Moving Average of a sequence is a common task in games (and other applications). The motivation is simple: if something happened too far in the past, probably it does not matter anymore.

One of the main problems with the standard average is that it “slows” over time. This can be a serious problem. Suppose that you are designing a game in which your player have to quickly press a button to keep a value (e.g., player speed) above a certain average. If you use the global average, after a certain amount of time, your player can stop pressing the button and still keep the average above the threshold.

The demonstration of this is quite intuitive. If you have an average a(t) at frame t and the player will not press anything in the current frame, the average at frame t+1 will be

This factor depends on the elapsed time and becomes “almost 1” very quickly. You don’t want that. You want to keep your player on the narrow land between “boredom” and “frustration”. You cannot give to your player the possibility to win without doing nothing for 30 seconds.

The solution to this problem is simple. Use a Moving Average. The player will have to push the button faster than the threshold, but the average is computed only using the data from the last 5 second (or any other time window you want).

YoshiX: Experiments made easy

Some months ago, I was frustrated by the monotony of the task of writing, running and collecting data from experiments. I was bored of facing always the same challenges, writing always the same code and facing always the same problems. In addition, every experiment ran on different platforms, and they quickly become difficult to replicate (and this should be the very point of every experiment).

Thus, I decided to write my personal framework for running experiments in Python: YoshiX. The idea behind YoshiX, inspired by classical Unit Testing libraries, is quite simple. You write your test in a separate file, then you run yoshix and it automatically finds every experiment in a specific folder, runs them, and collects the output in the format of choice.

It is a simple tool; I still have not spent a lot of time in it. But I think it has some interesting developments. Let’s look into some details.

The most promising languages of 2016

It is time to update one othe most popular article in this blog. It is time to talk about the most promising languages of 2016! But first, let me repeat the small notice I did the last year. The languages I am listing below are not the most used languages, or the languages that you have to learn in order to find a great job as a developer. There are many more established languages that fill this role. Languages such as C++, Java, C#, Python and JavaScript are way more solid and safe if you are looking for a job or to start a developer career.

Instead, I am trying to list emerging languages that may become more important at the end of 2016. This list is for you if: 1) you are passionate about programming languages 2) you want to learn something new because you are bored with your current language 3) you want to bet on a language hoping that it will become mainstream (and thus, you will be one of the early experts in that language, and this implies nice job opportunity). Or you can read this list because you are simply interested on where the language research and development is going in the real world (academic research is a totally different story).

Secret Guide!

Congratulations! You discovered the secret guide!

Press ? to show/hide this guide!